Interview with Michael Rubloff

In this episode, we delve into the world of neural radiance fields (NeRFs) with Michael Rubloff. We discover how NeRFs are revolutionizing 3D technology, the differences from traditional photogrammetry, and their potential in spatial computing and XR.

What are Neaural Radiance Fields (NeRFs), and how are they fundamentally different from photogrammetry?

Michael Rubloff: NeRFs, or neural radiance fields, were invented in 2020. I discovered them in early 2022 and dediced to start the website neuralfields.com to document the evolution of this new technology. NeRFs are the first iteration of radiance fields, which have now expanded into more varieties such as 3D Gaussian splatting. NeRFs are trained through a neural network, and unlike photogrammetry, they can process light information, including reflections and shadows, to achieve a lifelike quality. Photogrammetry has immense commercial applications and has been extensively developed over the last half-century, but NeRFs and radiance fields are completely new, offering features that weren't previously available. On top of that NeRFs are faster and produce more realistic outputs.

You mentioned that NeRFs are faster. Is that in both capturing the data and processing them?

Michael Rubloff: For the actual capturing stage, it depends. If you're creating an object using NeRF, it shouldn't take more than a couple of minutes to capture. If you're using a drone to capture a larger area, it might be similar in length to photogrammetry. However, when running the data through a structure-from-motion method and then into a tool capable of creating a NeRF like Luma or Polycam, you're only looking at about 15-20 minutes to see the final product, which is really fast compared to “standard” photogrammetry.

What got you into this field? What is your background?

Michael Rubloff: I discovered NeRFs while experimenting with the LiDAR scanner on my iPhone 12 during the pandemic and this led me into a multi-year deep dive into 3D scanning. I wanted photo-realistic captures, especially of people, and initially thought LiDAR was the answer. In early 2022, I found a post about instant NGP, which was exactly what I was trying to achieve. Without a computer, I borrowed one from a friend and bought a 3080 GPU. After a lot of trial and error, we captured thousands of NeRFs and learned best practices. There were no resources available initially, so it was critical for me to figure it out.

What were some of the learnings you had throughout this journey of capturing over 2,000 NeRFs ?

Michael Rubloff: It's almost better to not overthink things in some ways and be able just to go out and shoot. Having certain camera settings and focal length is really helpful. Shoot as wide as you can, use a fisheye lens if possible, and have a deep depth of field. A fast shutter speed is critical. Sharp and clear images are essential. Introducing parallax by moving in an arc or a circle helps the scene be understood better.

What about the processing of the data? How does that work?

Michael Rubloff: We've been fortunate to see no-code platforms like Luma AI and Polycam emerge, where you can drag and drop images into a web browser or upload them from your phone. If you're using platforms like NeRF Studio or instant NGP, you'll need some familiarity with the command line. Pre-processing is crucial, where the structure-from-motion stage aligns all the images in a dataset to understand their spatial arrangement. Methods like Colmap, with settings like sequential or exhaustive, help in this stage.

Do you prefer using web platforms like Luma and Polycam, or do you lean more towards PC-based methods?

Michael Rubloff: My approach is a bit all over the place because I try to put them through as many platforms as I can simultaneously. For ease of use, definitely Luma and Polycam are the easiest. However, I love using instant NGP because you can watch the 3D scene develop from nothing, which feels similar to watching a film photograph develop in a darkroom. It is a very satisfying experience.

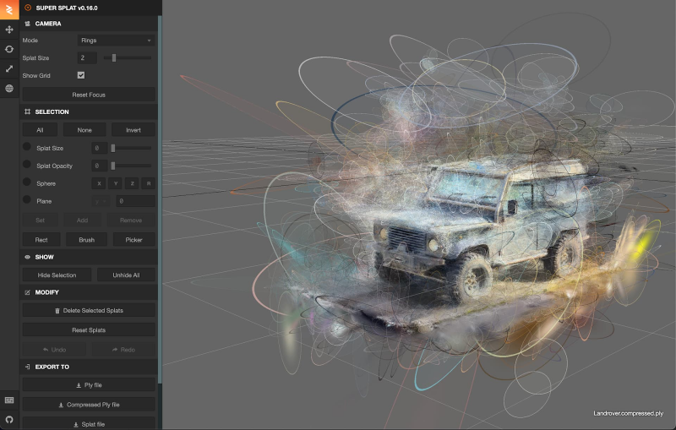

How do you actually edit and clean the NeRFs and Gaussian splats?

Michael Rubloff: NeRFs are not as editable just yet, but if you use instant NGP, you can go into VR and edit floaters using hand controllers. For Gaussian splatting, there has been a lot of work in terms of editing and creating viewers to put them into a web browser. Platforms like PlayCanvass, SuperSplat, and viewers by creators like AnyMatter15 allow you to take the resulting files and edit them. Apps like Kiri Engine also have in-house editors for removing floaters.

What are the steps to seeing these NeRFs and splats in VR?

Michael Rubloff: It's somewhat straightforward. For NeRFs, you train the NeRF in instant NGP and then connect through Steam Link with your headset. For Gaussian splatting, there's a platform called Gracia VR, which allows you to view splats in VR. Luma also supports VR through their webGL library, enabling virtual reality viewing of splat files.

How do you see NeRFs contributing to spatial computing and XR?

Michael Rubloff: They are directly linked with one another. There's been a large shift in priorities towards embracing spatial computing from larger tech companies. NeRFs will be a versatile tool for these companies, benefiting customers who can experience 3D environments. Potential applications include VR-based training, where trainers can provide lifelike demonstrations, and educational tools, where students can observe surgeries and other complex procedures in a 3D environment.

Where do you see this technology going in the future?

Michael Rubloff: The future of this technology is very exciting. It might be possible to have NeRFs be instant, where you press the shutter on your phone and instantly have a 3D scene. The ceiling on the technology is not limited by fidelity but by compute and engineering capabilities. Papers like VR NeRF from Meta show that IMAX-level quality NeRFs are achievable, and as technology continues to improve, the possibilities are limitless.